In my time working with students, I have always found it interesting to note what to them constitutes writing. They often equate writing with school writing exclusively, and, even at that, believe that only formal research papers rise to the level of real writing. It often never occurs to them to consider the plethora of activity that goes on throughout a course or via texting and Facebook outside of school as, well, writing. And yet it is.

Collapsing those arbitrary perceptual boundaries can open up a broader understanding of writing for students. Let me explain how.

Collapsing those arbitrary perceptual boundaries can open up a broader understanding of writing for students. Let me explain how.

Email did not exist when I attended college nor did it exist at Longview when I began working here. I received no formal instruction in how to write an email and yet I spend hours each day producing them since emails are currently the salient communication tool of the workplace. How did I learn to write in this new genre? In part, by applying what I had learned in graduate school about analyzing rhetorical situations.

That is, I considered the audience to whom I was writing and what they needed to know and crafted the message from there. Emails follow a pretty distinct pattern, so much so that the template was eventually built into the software. The writer, of course, controls what gets plugged into that template, so reading emails was a good way to see which features were promoted and tolerated in an academic workplace. Another important part of my learning was observing others and imitating their rhetorical moves.

Our students will similarly learn some of the writing nuances of their particular work setting while on the job. At a four-year school, most will have opportunities to rehearse the kinds of professional writing they will be called to do post graduation. For future health professionals, that means care plans and charting. For would-be engineers, it means technical reports and proposals. For those going into business, it means memos and reports that reflect brevity and clarity. In that world, after all, time is money, so no one wants to waste it reading unnecessarily lengthy or arcane communiques.

Will email still be the communication tool of choice by the time current students graduate and enter the workforce? Quite possibly. Or email could be supplanted by a later, greater technological advance that sends it the way of the telegram. What's important is not that we teach students to write emails or texts, but that we give them ample opportunity to learn through writing and, in doing so, help them develop enormous depth and breadth as communicators so they can accurately decipher any writing situation they find themselves in.

Our students are navigating different writing arenas throughout each day. They slip between these much the way all of us do when we adjust our manner of speaking when with friends as opposed to a room full of strangers. Linguists refer to this phenomenon as "shifting registers."

We typically dress and speak differently in the context of a job interview than we would in the context of talking to neighbors while doing yardwork. We recognize that these two situations make strikingly different demands of us as communicators. Our ability to see these differences hinges on our understanding of the expectations of job interviews and our understanding of the expectations of informal chatting. The more you know about those expectations, the more likely you are to get your message across efficiently and effectively.

Helping students understand that academic writing requires a clarity and explicitness they are not necessarily obligated to when texting or posting on Facebook is a first step in helping them understand the expectations of the academic audience.

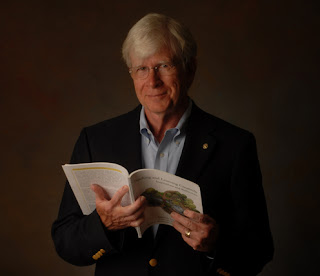

Art Young, a WAC pioneer who hailed from a disciplinary background of Engineering and English literature, distinguishes in Teaching Writing Across the Curriculum between personal writing for learning which privileges the language and values of the writer and public writing for communicating which privileges the language and values of a broader discourse community (Prentice Hall Resources for Writing, third edition).

|

| Dr. Art Young, Clemson Professor, holding his book Teaching and Learning Creatively, which is used by a number of WAC faculty at MCC-Longview and available for borrowing through the WAC Program. |

Whether in school or out of school, whether for close associates or for publication, it all qualifies as writing. So the question becomes: How effective is any message? Clearly, that depends a lot on who is reading it. The sooner students grasp the concept of audience, the sooner they will become discerning writers.

And since technologies associated with reading and writing are bound to change more than a few times in their lifetimes, our best bet is to prepare students to analyze every writing situation they encounter, including the ones we create.

So when and where did you learn to write an email?